Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L: a lens dedicated to architecture

Since 2016, tilt-shift lenses have taken on an increasingly important role in my architectural photography. After working with large format view cameras, Nikon PC-E lenses and a first-generation 24mm TS-E, I eventually settled on the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L, mounted on my Nikon Z bodies via a Fringer EF-NZ II adapter. In this article, I look back at that journey, the reasons behind this choice, and how this 17mm has become my main tool for correcting perspective and composing directly at the time of capture.

From 4×5" view cameras to tilt-shift lenses

At the beginning of my career, tilt-shift lenses for 35mm were rare. At Nikon, the main options were the 28mm and 35mm PC (Perspective Control). Architectural photographers mostly worked with bellows view cameras, which allowed the front standard (lens) and rear standard (film plane) to move independently to correct perspective.

My first architectural images were therefore either details framed with telephoto lenses, more distant views to limit distortion, or deliberately assumed wide-angle low-angle shots. On modern buildings, these converging verticals can become an interesting graphic choice, but on historic monuments the result is sometimes less satisfying.

In 1993, I borrowed a Canon TS-E 24mm f/3.5 from Canon Pro to test it in Hong Kong, a city of vertical lines par excellence, during a transit day on my way to an Indycar report in Surfer’s Paradise on Australia’s east coast.

That same year, I bought a 4×5" Sinar view camera with two Schneider lenses (90mm and 150mm). This equipment offered extraordinary possibilities in terms of perspective control… at the cost of heavy logistics and a working pace far removed from reportage.

In practice, the frequency of my motorsport assignments for agencies quickly caught up with me: the Sinar mostly served for one trip in the American West, a few outings in Paris to photograph monuments, and a single studio session before ending up in a closet and finally being sold.

I only came back to lenses with movements much later, in 2016, with a Nikon Nikkor 85mm f/2.8 PC-E used mainly in the studio for portraits and still life. As often happens in photography, selling that lens then helped finance the next one.

Why a 17mm tilt-shift for architecture?

In dense urban environments, capturing an entire building often means working at ultra-wide angles. For several years, I used an Irix 11mm f/4 to frame wide, at the cost of an oversized foreground and uninteresting empty areas at the bottom of the image. Even with post-production corrections, these images remain marked by a perspective that can sometimes be hard to read.

The Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L addresses precisely this issue: it combines a diagonal angle of view of 104° (even wider than a 19mm) with the ability to shift the lens. Instead of tilting the camera upwards, you keep the body perfectly level and “raise” the image in the frame using shift. The result: verticals stay straight, the building no longer appears to lean backwards, and the foreground regains natural proportions.

Indoors, especially in cathedrals and churches, this 17mm allows you to render the full scale of the nave, the height of the vaults and the geometry of the columns without sacrificing straight vertical lines. Where a conventional ultra-wide angle forces compromises, the TS-E 17mm offers precise framing directly at the time of capture.

Why the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L instead of the Nikon 19mm PC-E?

Before settling on this 17mm, I explored several options. In 2023, wanting to improve my architectural work, I tried a first-generation Canon TS-E 24mm f/3.5 mounted on a Nikon Z5 via a Viltrox EF-Z adapter during a trip to Vietnam. The optical quality of this early version, acceptable on film in the 80s and 90s, showed its limits on modern high-resolution sensors. What we used to judge with a simple Schneider loupe now appears much more critically at 100% in Lightroom or Photoshop.

I then looked at and tested several lenses: two copies of the Nikon 24mm f/3.5D ED PC-E, neither of which convinced me, as well as a Laowa 15mm with an element alignment issue, even after a trip to the service center. In the era of high-resolution mirrorless cameras, a few optical flaws or an average sample quickly become deal breakers.

In the end, the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L won out. I now use it with a Fringer EF-NZ II adapter on my Nikon Z8 and Z7 II, and I’m very pleased with the combination. One question comes up often: why not choose the Nikon 19mm PC-E instead?

The answer is simple: budget. The Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L was available at around €1,000 used, roughly half the price of a used Nikon 19mm PC-E. Add to that a wider angle of view and proven optical quality, and the trade-off becomes very rational for a practice where the lens remains a tool rather than an object of worship.

I also use the Fringer EF-NZ II adapter with a Canon EF 300mm f/2.8 L USM (non-IS).

In the field: cathedrals, religious buildings and urban architecture

The natural playground for the TS-E 17mm is the interior of religious buildings and imposing architecture in cities. In Pontigny, Westminster, Le Havre or Notre-Dame de Bernay, being able to correct perspective in-camera lets me focus on the light, the rhythm of the columns, the volumes and the relationship between the space and the people moving through it.

Rather than multiplying frames for a vertical panoramic stitch or relying on heavy software corrections, I can decide exactly where to place the base of the image, how much floor to show, and how much space to leave around the vault or a stained-glass window. This approach extends the discipline of shooting slide film that I grew up with: what you see in the viewfinder should be as close as possible to the final result.

Outdoors, the TS-E 17mm is just as valuable for photographing modern buildings, glass façades or business districts such as La Défense. Controlling the verticals lets you compose highly graphic images without being forced to live with the natural distortion that comes with low-angle shots.

Handling and hand-held shooting with the TS-E 17mm

Contrary to what people often imagine about tilt-shift lenses, I use the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L mainly hand-held. In many religious or historic buildings, tripods are banned for safety reasons, to avoid visitors tripping over them. Modern mirrorless cameras, with clean high-ISO performance and in-body image stabilization (IBIS), make it possible to work hand-held at shutter speeds around 1/15 s, which is perfectly realistic in the field.

The TS-E 17mm comes with a large bayonet-mount cap, a deep rigid-plastic cover whose depth effectively protects the very prominent front element. Seen from the front, that element almost deserves the nickname “HAL 9000”, a nod to the computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey, shown on screen through a Nikon 6 mm fisheye lens, while the cap itself is more reminiscent of a round cheese box. A wrist strap lets you let this bulky cap hang from your wrist during shooting, instead of having to put it away every time you reframe.

On the Nikon Z8, the virtual horizon is extremely precise and the stabilization is very sensitive. The slightest micro-movement as you try to align the horizontal indicators can sometimes be overcompensated by the camera, making fine alignment tricky. Two approaches help here: temporarily disabling stabilization while adjusting the framing, and holding your breath at the moment of exposure to limit any unwanted movement.

My working method is as follows: I first position myself along the main axis of the nave in a cathedral, or perfectly perpendicular to the façade I want to photograph. I unlock the shift lock, roughly frame the scene, then switch to manual focus. Next, I refine my composition by aligning the virtual horizon indicators, then turn the shift knob to move the front of the lens until I get the framing I want, with nicely corrected verticals.

Because of the lens’s very wide angle of view, full-frontal views are often preferable to avoid an excessive disproportion between the foreground and the most distant plane. This is particularly noticeable on some modern architecture images, such as the Centre Pompidou photograph in the gallery at the end of this article, where you can fully exploit the width of the field while keeping a readable geometry.

Creative tilts: isolating a subject while correcting converging lines

Beyond simple perspective correction, the tilt movement opens up interesting creative possibilities. On subjects like the Pouce de César in La Défense, tilting lets you reduce depth of field to isolate the sculpture while simultaneously adjusting the shift to keep the verticals of the background buildings perfectly straight.

This combined tilt + shift adjustment takes a bit of practice, but it offers very fine control over how the viewer’s eye moves through the frame. Where a conventional ultra-wide angle tends to render everything sharp and sometimes a little “flat”, the TS-E 17mm allows genuine plane of focus control or, on the contrary, selective blur on architectural subjects.

Technical specifications of the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L

| Specification | Detail |

|---|---|

| Angle of view (horizontal / vertical / diagonal) | 93° / 70°30’ / 104° |

| Optical construction | 18 elements in 12 groups |

| Number of diaphragm blades | 8 |

| Maximum / minimum aperture | f/4 / f/22 |

| Minimum focus distance | 0.25 m |

| Maximum magnification | 0.14× |

| Dimensions (diameter × length) | 88.9 × 106.9 mm |

| Weight | 820 g |

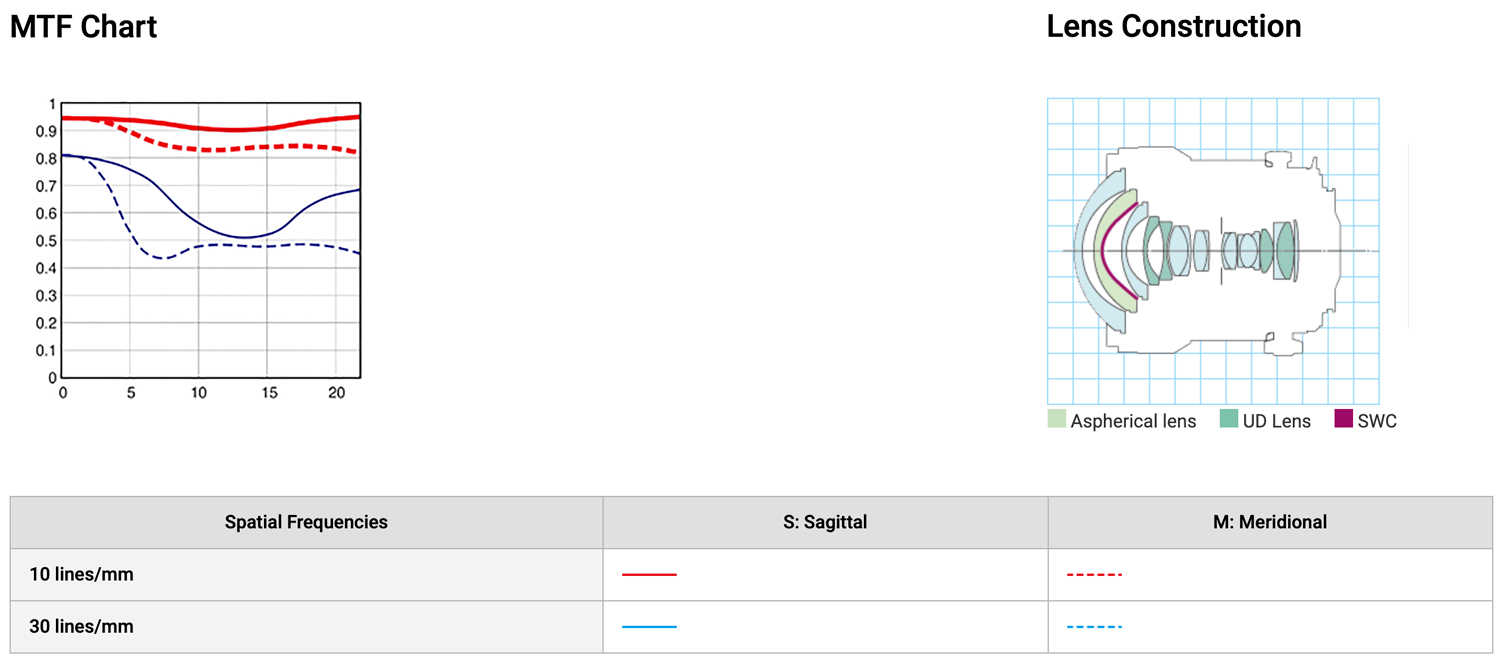

MTF charts and optical design

Is the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L worth the investment?

The Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L is not a mainstream lens. It is a specialized tool designed for photographers who want to control geometry and perspective directly at the time of capture, whether for heritage, contemporary architecture or demanding editorial projects.

For me, it has been a natural evolution after years of working with view cameras, PC-E lenses and conventional ultra-wide angles. Its very wide angle of view, optical quality and the option to use it on my Nikon Z bodies via a Fringer EF-NZ II adapter make it an ideal companion for my architectural series.

If you only photograph buildings occasionally and are happy with software corrections, this lens will probably be overkill for your needs. But if you regularly work on architecture, interiors or heritage, and you want to get closer to the discipline of large format view cameras, the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L can be a key investment and a lens that will stay with you for many years.

Click on the photos below to view them full screen.

Toutes les photos de ce site sont protégées par copyright © Sebastien Desnoulez, aucune utilisation n'est autorisée sans accord écrit de l'auteur

All the photos displayed on this website are copyright protected © Sebastien Desnoulez. No use allowed without written authorization.

Mentions légales

FAQ

Is the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L compatible with Nikon Z mirrorless cameras?

Yes. With an EF to Z-mount adapter like the Fringer EF-NZ II, the TS-E 17mm can be used on Nikon Z bodies (Z5, Z6, Z7, Z8, etc.) with full manual focus and tilt/shift functionality.

Can you shoot handheld with a tilt-shift lens?

Absolutely. With modern mirrorless bodies like the Nikon Z8 and Z7 II featuring IBIS and precise horizon indicators, it's possible to shoot handheld at 1/15s while maintaining perspective correction.

What’s the benefit of the shift function?

It allows you to correct vertical distortion without tilting the camera. You can frame tall buildings or interiors while keeping vertical lines straight, which is essential in architectural photography.

Why choose the Canon TS-E 17mm f/4L instead of the Nikon 19mm PC-E?

The Canon 17mm is wider and more affordable on the used market. While the Nikon 19mm PC-E offers slightly more modern optics, it’s significantly more expensive. The 17mm remains a practical and cost-effective choice.

Do you need a tripod to use a tilt-shift lens effectively?

Not necessarily. With image stabilization and proper technique, handheld use is entirely feasible, especially when tripods are not allowed in historic buildings or museums.

About the author

Sebastien Desnoulez is a professional photographer specializing in architecture, landscape and travel photography. Trained in photography since the 1980s, he has covered Formula 1 races and reported from around the globe before devoting himself to a more demanding fine art photography practice, blending composition, light and emotion. He also shares his technical expertise through hands-on articles for passionate photographers, built on a solid background in film and digital photography.

Tags

I am represented by the gallery

Une image pour rêver