Film Photography Today: Creative Revival or Romantic Illusion?

Rediscovering old film archives, handling a Nikon F, or dreaming of a Graflex view camera, the vintage temptation draws in many photographers. But is it truly a return to the roots… or just a mirage?

Choosing a camera is already laying the foundations of your visual language. Over the decades, technological evolution has granted us increasing freedom: ultra-precise autofocus, high ISO sensitivities, extended dynamic range, lenses delivering sharpness edge-to-edge at full aperture, immediacy… all tools enabling us to explore creative territories that were once out of reach.

But should we, for that reason, reject the tools of the past? And how do we know whether the right choice today lies in returning to film, or investing in a full-frame or even medium-format digital camera? Here are a few reflections shaped by experience, to help informed enthusiasts consider the question with a broader perspective.

The charm of vintage gear

I used two Nikon F bodies from the 1960s for a long time, no light meter, prism viewfinder only. One accompanied me as a third body in my early days; the second, added in 1992 as my “color” body during my first road trip through the American Southwest, embodied an almost ascetic approach, in contrast with my digital EOS-1s on racing circuits.

I sold both for around €200 each to fund my Nikon Z lenses. Same for my Nikon F5, the most advanced film camera I ever worked with, which I ended up selling after more than fifteen years of sleeping in my camera bag. Rational decisions… yet not without a twinge of emotion.

There’s something about these tools: functional beauty, timeless robustness, an almost lost elegance, and, with the Nikon F, the satisfaction of making the photograph “by hand”: focus, shutter speed, aperture, helped by a Minolta light meter… and a raw body so solid it felt like you could hammer nails with it.

Today, I still own a 1968 Nikon F Photomic, inherited from my father in 2018, and yet I’ve never loaded a single roll of film into it.

Archives, memory, and regrets

Since starting the digitization of my photo archives, with images taken since 1984, I feel more connection than nostalgia. Each image brings back a place, a light, a camera, a situation. It's as much a mental map as an emotional one.

My only regret, perhaps, is that I sometimes photographed with image banks in mind: perfect framing, “sellable” images, but so few photos of the surrounding context, the streets, the life. New York in 1985, Paris in the late 1980s… I brought back clean shots, but I should have captured more of the city’s atmosphere. That said, with only 36 exposures per roll, we rationed every frame.

Between the lure of a compact and a return to the roots

Recently, I too felt tempted by a partial return to film, not out of nostalgia, but to reawaken something. I thought about picking up my Nikon F again, mounting a 24 mm lens, loading a roll of HP5, and shooting a film, just like between 1985 and 2000, to find a mindset, a rhythm, an alternative creative mode.

At the same time, I considered buying a small camera I could always have with me. I explored the idea of a Canon EOS M with its 22 mm lens (35 mm equivalent), a simple and efficient setup. I also looked at high-end compacts like the Leica D-Lux 8, its twin Panasonic LX100 II, the Sony RX100 V, and the Canon PowerShot G5 X Mark II, all offering bright lenses, discreet bodies, and electronic viewfinders.

The desire was there: image quality beyond what my smartphone offers, with pro-like ergonomics in a compact body that fits in a pocket.

But very quickly, I reconsidered. Why invest in a system that, as appealing as it may be, imposes compromises? When I go out with my bag, my Z lenses, and my cameras, I know I can shoot anything, with the quality and precision I expect. Technical flexibility isn’t a luxury; it’s a condition for creative freedom. And that realization also fed the desire to write this article.

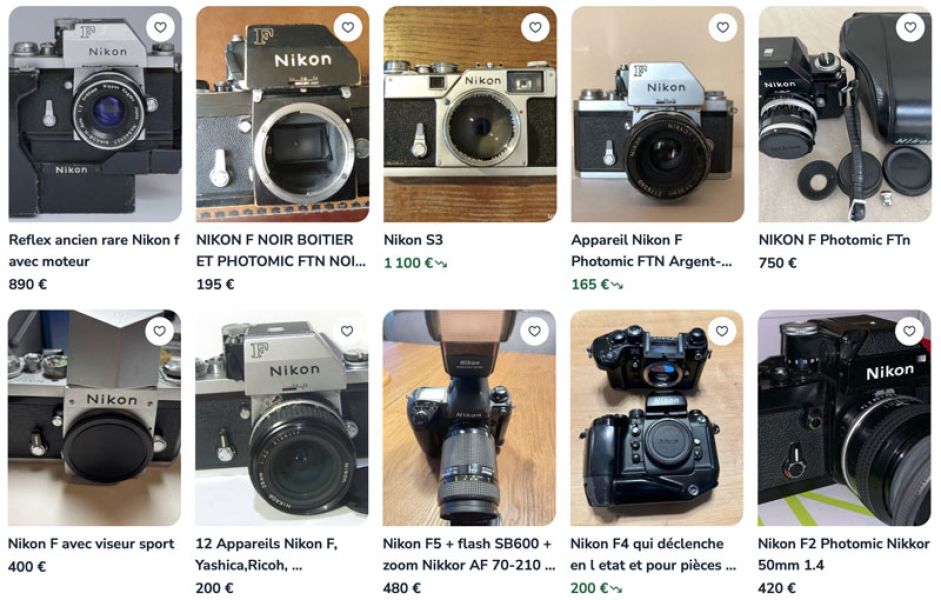

The ruined temple of film photography

Beirut, Place des Canons, October 1991 - On the left, the making-of by Fabrice de Pierrebourg; on the right, my photograph shot with a Nikon F and an 18 mm f/4 on Ilford HP5. Photo: © Sebastien Desnoulez

Beirut, Place des Canons, October 1991 - On the left, the making-of by Fabrice de Pierrebourg; on the right, my photograph shot with a Nikon F and an 18 mm f/4 on Ilford HP5. Photo: © Sebastien Desnoulez

From time to time, I browse second-hand listings as a mental exercise, a way of imagining myself using a Nikon F, a Hasselblad 500, a Fuji 6x9, a Graflex view camera, or a Zenza Bronica. But each time, reality catches up: developing film, scanning it, archiving it… all of that takes time I no longer have.

I learned photography the hard way, shooting film in every condition, sometimes up to twenty rolls a week during my ten most intense agency years. Today, I enjoy being able to free myself from a technique I’ve mastered, so I can focus fully on the subject: how to showcase it, how to interpret it in my own way.

I also sometimes revisit old issues of Photo Reporter, the magazine that made me want to become a photojournalist, I recently bought about forty back issues. Page after page, the graveyard of defunct brands grows. Behind every ad or camera test, you can see an entire profession erased, once-specialized trades now obsolete, with a few colleagues among the last to have practiced them.

Using a Leica III or a Rolleiflex today is a bit like driving a vintage car on a modern highway: the experience is unique, but it requires different reflexes, and it’s not suited to every context. It won’t transport you to Paris in the 1950s. It won’t make you travel through time, any more than it will turn you into Doisneau or Cartier-Bresson just because you’re holding the same kind of camera.

At best, this gear gives your images a strong aesthetic, a nostalgic “form” that can feel out of sync with the “content” of what you’re photographing. A delicious illusion, perhaps, but an illusion nonetheless.

It’s not the camera that makes the photograph

Of course, in a deliberate artistic approach, constraints can boost creativity. But in everyday practice, why impose technical limits? Why risk missing a shot because the lens isn’t bright enough, or the film doesn’t have sufficient ISO sensitivity?

Budget can be a factor, of course. But in this era of massive transition from DSLRs to mirrorless, the second-hand market is full of gems: a Nikon D800 for €500, a 14-24mm or 70-200mm f/2.8 for €400, far more reliable and capable than many film cameras from the 1970s.

Trends and social media

So why this renewed popularity of film? For some, it’s a way to learn the fundamentals, a respectful starting point, and that deserves recognition. For others, it’s a kind of aesthetic filter: a vintage look guaranteed by expired film and a Hanimex lens with color aberrations… that no one wanted in the 1980s!

This is not about judgment. Photography remains a language. Whether using medium format or Micro Four Thirds, a Rolleiflex or a Z8, the gear doesn’t create emotion. The eye, the mind, and the heart do. The rest is just interface.

I also understand that for some, these limitations are part of the pleasure: they enforce a rhythm, attention, and a certain intimacy with the subject. And that, too, is the beauty of the process.

I truly respect those who love vintage objects, classic cars, or old cameras, and take pleasure in using them. My point is not to criticize or discourage, but to explain that if what you’re seeking is immediacy, technical performance, and the freedom to create in any situation without worrying about hardware limitations, then film may constrain you more than it liberates you.

To continue exploring this topic, you might enjoy this article: 40 Years of Photography: From Film to Digital and Mirrorless.

Today, film and digital photography are not enemies, one is the continuation of the other. From glass plates to digital sensors, from black-and-white film to color, photography has constantly adapted to the tools of its time. What truly matters is not the technique used, but how it serves a vision.

Many photographers now combine both worlds: film shooting, scanning, digital retouching, inkjet printing. The tools evolve, but the photographer’s eye remains essential, whether we develop our images in a darkroom or on a screen.

Choose film photography if you feel truly drawn to it, maybe for personal reasons, because someone gifted you a camera with sentimental value, or because you believe learning photography should start there. If so, why not begin with a slide film (positive transparency), whose narrow exposure latitude will push you to improve faster… by learning from your mistakes?

About the Author

Sebastien Desnoulez is a professional photographer specializing in architecture, landscape and travel photography. Trained in photography in the mid-1980s, he covered Formula 1 races and reported from around the globe before devoting himself to a more demanding fine art photography practice blending composition, light and emotion. He also shares his technical expertise through hands-on articles for passionate photographers, built on a solid background in both film and digital photography.

Tags

I am represented by the gallery

Une image pour rêver