40 Years of Photography - From Film to Mirrorless

For forty years, I’ve witnessed the radical transformation of photography, from fully manual film cameras to today’s most advanced mirrorless systems. Through my gear choices, field experiences, and the waves of technological change, this is a personal, technical, and human testimony that may help today’s photographers better understand what’s at stake when choosing between film and digital.

Table of Contents

- My Beginnings with Film

- Switching to the Nikon System

- The Pros and Cons of Shooting on Film

- Gear of a Photojournalist

- The Canon EF Era and Autofocus

- Back to Nikon and Early Digital

- The Demands of the Film School

- The Mirrorless Shift: Nikon Z

- Thoughts on the Film Revival

- Conclusion: Freeing Yourself from the Technical

My Beginnings with Film

Before my first trip to the United States, in 1985, I bought a second-hand Fujica STX-1N with a 50mm f/1.9 lens. What started as a simple way to bring back memories quickly turned into a deep passion for photography. The seller had loaded it with a roll of Fujichrome 100, a slide film known for its vibrant colors and narrow exposure latitude (-1 to +1 EV).

It was an excellent school for learning discipline: measuring light precisely, exposing correctly, and above all, composing directly in-camera. During cinema and photography classes at university in Texas, I discovered the incident light meter, using a Minolta Autometer III, far more accurate than the reflective metering from the camera’s internal meter.

This first experience laid the foundations for my photographic practice. Upon returning to France, I quickly felt the need for more reliable and versatile equipment. My father owned a Nikon F Photomic, so the brand naturally became the obvious choice.

Switching to the Nikon System

I purchased a Nikkormat EL-2, a 24mm f/2.8 and a 50mm f/1.8. I soon sold this body and bought a brand-new FM2 with a MD-12 motor drive, then added a second-hand FM body with a MD-11 motor as a backup.

The main drawback of film was the film constraint: fixed sensitivity, and the need to choose between color or black and white for 36 exposures. Two bodies were required, one for each film type. I used Fujichrome 100 or Velvia 50 for color, and Ilford HP5 400 ISO for black and white. Bright lenses were essential due to the low ISO sensitivity, the inability to change ISO, and the dim viewfinders, especially at apertures smaller than f/4. Despite manufacturers’ efforts, focusing screens darkened significantly beyond that point.

At the time, I had practically worn out my eyes studying the Nikon lens catalog, selecting the brightest prime lens in each focal length, all within a tight budget. Until the late 1980s, bright lenses were almost exclusively primes. There was a manual-focus Nikon 80-200mm f/2.8 zoom, but it was heavy, expensive, and bulky. Most zooms had much more modest apertures back then.

Download Nikkor Lenses Brochure 1984

On later trips to the U.S., I completed my original kit with a 35mm f/1.4 Ai-S and a selection of second-hand Nikon lenses: 85mm f/1.8, 180mm f/2.8 IF-ED, a Minolta Autometer III F light meter, and a 1960 Nikon F with prism finder and no built-in meter used immediately in Dallas Police 1987 - A photo report inside the patrols of NorthWest Dallas. This gear was far more affordable than in France, where the 33% VAT made photography a luxury product.

The Pros and Cons of Shooting on Film

Shooting on film meant dealing with strong constraints, but also developing solid reflexes. Here’s what it taught me on a daily basis:

Formative Benefits:

- Accurate metering was a must

- Precision framing at capture, little or no cropping afterward

- Better understanding of the ISO / shutter speed / aperture triangle

- Cultivating the "get it right in-camera" mindset, crucial for reportage

- Unique aesthetic qualities of analog rendering, especially slides and black and white

- Lightweight, compact gear: no AF motors or stabilization meant smaller, lighter lenses

Main Drawbacks:

- Fixed ISO sensitivity for the entire roll (20, 24, or 36 shots)

- Switching from B&W to color required a second body

- Very narrow exposure latitude with slides (about ±1 EV)

- No instant feedback, results were only visible after development

- Color stability over time depended on how well the lab managed its chemistry

- The cumulative cost: film, development, prints, or scans

In agencies, slides were judged as-is, no editing, no margin for error. In black and white, many professionals printed with the negative’s black border showing, proof that the frame was perfect from the start. The Leitz Focomat V35 enlarger had a slightly larger negative holder so the black edge would appear on the final print. Being precise and fast wasn’t optional, it was a basic requirement for survival in the field.

The Photojournalist’s Equipment

In 1987, I carried the standard photojournalist’s kit: two motorized bodies along with 24mm, 35mm, 50mm, 85mm, and 180mm lenses. I began using flash for reportage, learning semi-automatic exposure control: if the flash was set for f/4, I would adjust the aperture by half a stop depending on the subject’s brightness (opening up for light subjects, stopping down for dark ones).

I then acquired a Nikon 400mm f/3.5 IF-ED, which allowed me to shoot from the press stands during race weekends and take my first steps in sports photography, especially in motorsports. This equipment served me well during assignments for DPPI press agency between September 1988 and late 1990.

Learning motorsports photography with fully manual cameras and lenses proved to be incredibly formative.

Within a few years, the market changed rapidly. The arrival of autofocus disrupted habits, and manufacturers entered a race for performance.

The Canon EF Era and Autofocus

In the late 1980s, Canon released the EOS-1 with efficient autofocus, while Nikon struggled to convince with the F4. Around 1991, we began to see new photographers on the racing circuits, especially in Formula 1, equipped with Canon EOS-1 cameras, drawn by the ease autofocus offered when learning to track fast-moving cars.

The DPPI agency switched to Canon EF. I sold part of my Nikon gear to buy two EOS-1 bodies with booster grips, a 50mm f/1.8 EF, the 20–35mm and 80–200mm f/2.8 zooms (the latter with terrible vignetting), a 300mm f/2.8 USM, and both 1.4x and 2x teleconverters. The agency made available two 500mm f/4.5, a 600mm f/4, and a 400mm f/2.8, which I always used handheld.

In parallel with this switch to the EOS system for professional reasons, I continued practicing a more personal, raw, and traditional kind of photography. I kept two Nikon F Eyelevel bodies from 1960, an F2AS, an 18mm f/4, and my 24mm, 50mm, and 85mm lenses. These fully mechanical, compact, and reliable cameras followed me everywhere, on work trips and holidays alike.

This slower approach relied on manual focusing and incident light metering with a handheld Minolta Autometer III F or Sekonic L308 meter. A deliberately thoughtful practice, now known as slow photography.

In this spirit, I purchased a Sinar 4x5" view camera in 1993, with which I created a few images of the American West and Parisian landmarks.

In early 1995, I tested a new approach to combine discretion, compactness, and slow shutter speeds handheld. For a few months, I used a Leica M6 with a 28mm f/2.8. But the trial was not convincing:

- the lens hood blocked the lower right quarter of the viewfinder,

- the viewfinder, affected by barrel distortion, didn’t suit my style based on precise framing and geometric alignments in urban scenes. It was impossible to check whether the camera was perfectly level.

Despite the absence of a mirror, theoretically allowing 1/4s handheld exposures without vibration, these flaws proved disqualifying.

Return to Nikon and First Steps into Digital

In 1997, I returned to Nikon with a F5, a 24mm AF-D, an 80–200mm f/2.8 AF-S, a 300mm f/2.8 Ai-S, a 500mm f/4 Ai-P, and a TC-14, complementing my existing lenses. On the track, we would manually preset the focus on Canon EF lenses based on the cars’ racing lines for action shots, so using Nikon manual-focus telephoto lenses made perfect sense.

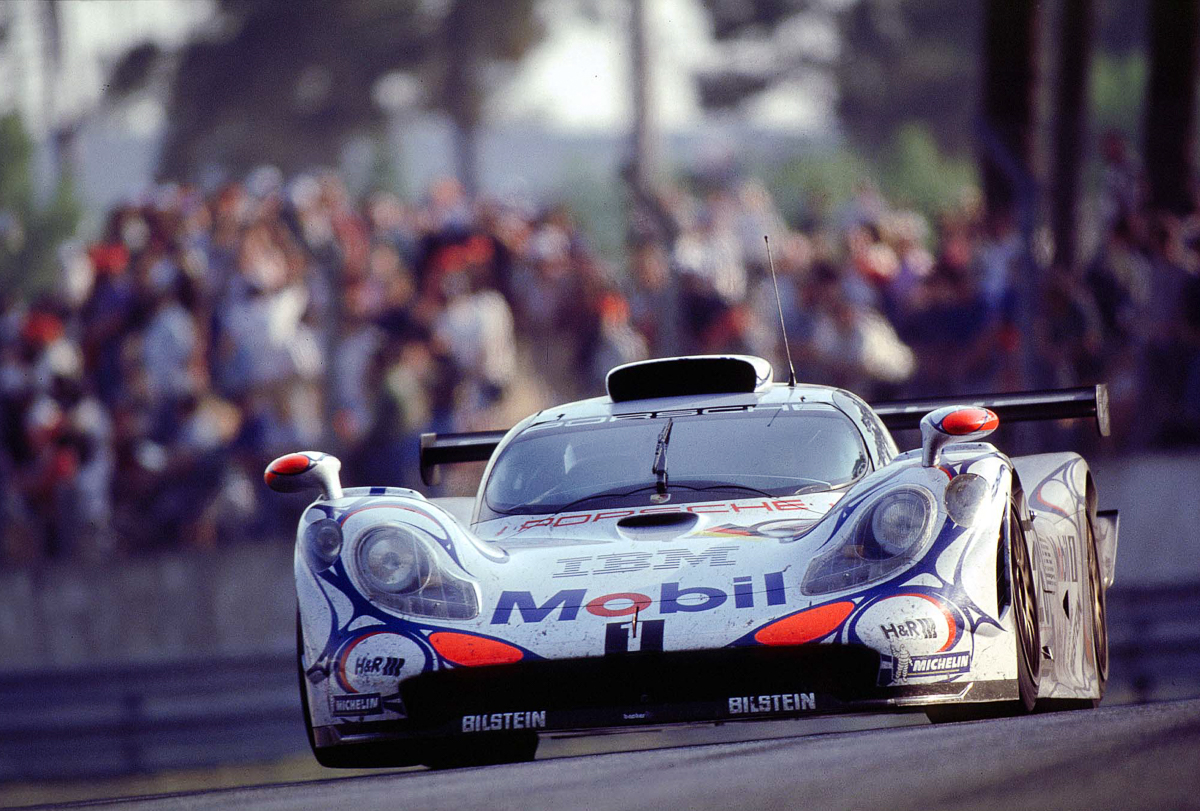

The photo of the Porsche 911 GT1-98 on three wheels at the 1998 24 Hours of Le Mans was in fact taken with the F5 and the 500mm f/4 Ai-P + TC-14, giving a 700mm f/5.6 setup with manual focus.

At the same time, in 1996, I created the agency’s digital photography department and developed the digitizing and distribution workflow for our photo reports, using a Nikon LS-2000 + SF-200 scanner.

To improve productivity, we invested in the first DSLRs: the Kodak DCS-3 (1.3 MP, with a strong magenta cast), followed by the more convincing DCS-520 (2 MP). In Indianapolis, I tested and recommended the Nikon D1 (2.7 MP), initiating the agency’s shift to digital photography using Nikon mount equipment.

The Demands of the Film School

For about ten years, I was shooting around 30 rolls of film per week. I developed my personal black and white films in Paterson tanks and printed my negatives on RC or fiber-based paper. This demanding self-training taught me to photograph instinctively, without relying on automation or post-processing.

After the agency was liquidated, I returned to freelance work: corporate portraits, studio, architecture, and interior design. I gradually re-equipped myself with Nikon full-frame DSLRs (D610, D800). Processing my architectural photos in Lightroom, taken with the 18mm f/4 Ai and 24mm f/2.8 AF-D, revealed their optical flaws, moustache distortion for the former, barrel distortion for the latter. I eventually replaced them with a wide-angle zoom and continue to gradually upgrade my gear.

The Mirrorless Shift: Nikon Z

The switch to the Nikon Z mirrorless system in 2021 allowed me to free myself even further from technical constraints. Thanks to high-performing sensors and in-body stabilization, I can now shoot handheld in extremely low light, with lenses used wide open, without compromising on sharpness or resolution.

The metering system is exceptionally reliable. I mostly shoot in Aperture Priority (A) mode combined with Auto ISO. Some may view this as heresy, but my experience justifies it fully. This setup lets me focus entirely on the subject, the light, and the composition, rather than fiddling with technical settings.

I shoot exclusively in RAW to take full advantage of the sensor’s dynamic range during post-processing in Lightroom. I switch to Manual mode only for long exposures with ND filters or in special cases where I spot-meter on a precise area of the landscape, usually the brightest zone.

I mention Nikon Z because it’s my current system, but other mirrorless options, Canon, Sony, Fuji, Panasonic, offer equally impressive results depending on your needs and preferences.

Over the years, I’ve used a wide variety of photographic systems: manual and autofocus Nikon, Canon EF, Mamiya RB67, RZ67, Mamiya C330, Leica M6, and even large-format view cameras.

In the studio, I worked with Balcar, Broncolor, Elinchrom, and Profoto flash systems, and used specialized lenses like the Canon TS-E 17mm and 24mm, or the Nikon PC-E 85mm for architectural photography. This technical diversity has allowed me to assess the strengths of each system depending on real-world constraints and use cases.

I chose the Nikon Z system over medium format for several reasons. At equivalent focal lengths, it offers more compact setups, a wider range of faster lenses, and zooms covering more focal lengths. The 45MP sensors in the Z7II and Z8 provide more than enough resolution for large-format prints. And there’s a key economic factor: far lower cost for equivalent image quality.

Photography is about capturing and shaping light. The medium doesn’t matter much. But digital tools offer unmatched precision, and help reduce environmental impact by eliminating film development chemicals.

Thoughts on the Film Revival

The Allure of Film – Camden Market

I understand the current fascination with film’s imperfect aesthetic, often seen as a return to “authentic” photography. Yet film imposes demanding technical constraints: narrow exposure latitude, need for anticipation, development costs, etc. These come on top of the usual challenges of learning photography and can make the path harder than expected for beginners exploring film.

What I find more puzzling is the paradox of shooting film, having it developed and scanned by a lab, viewing the results on a state-of-the-art iPhone, and then abandoning the negatives. In New York, some labs don’t even know where to store unclaimed film anymore. I’ve read several reports confirming this trend, and heard the same from a professional printer in Paris.

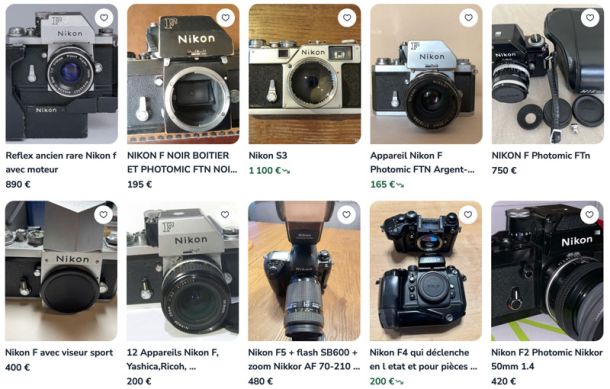

There’s also a noticeable rise in the price of used film gear, with no guarantee of functionality or reliable results.

I won't try to influence anyone to choose between film and digital, nor engage in sterile debates with those who present opinions as universal truths. It's a personal, often generational, choice.

Conclusion: Freeing Yourself from the Technical

What truly matters is that film brings a unique aesthetic, one that Fujifilm now emulates through built-in film simulations on its digital cameras. But that distinctive look won’t make you a better photographer. No medium, however noble, can make up for a lack of vision or solid technical foundations.

My only use of film today is artistic, with Lo-Fi cameras like the Holga or Lubitel, to experiment and provoke accidents. I choose digital not for convenience, but for the freedom it offers. And I return to film when I deliberately want to let go of control.

Double exposure – Holga on Fuji film – Jardin d’Acclimatation, Paris – 2005 – Photo: © Sebastien Desnoulez

Whether it’s freezing motion on a racetrack, building rigorous perspectives in architecture, or embracing chaos with a Holga, perhaps what matters most is keeping your eye curious, free, and alive.

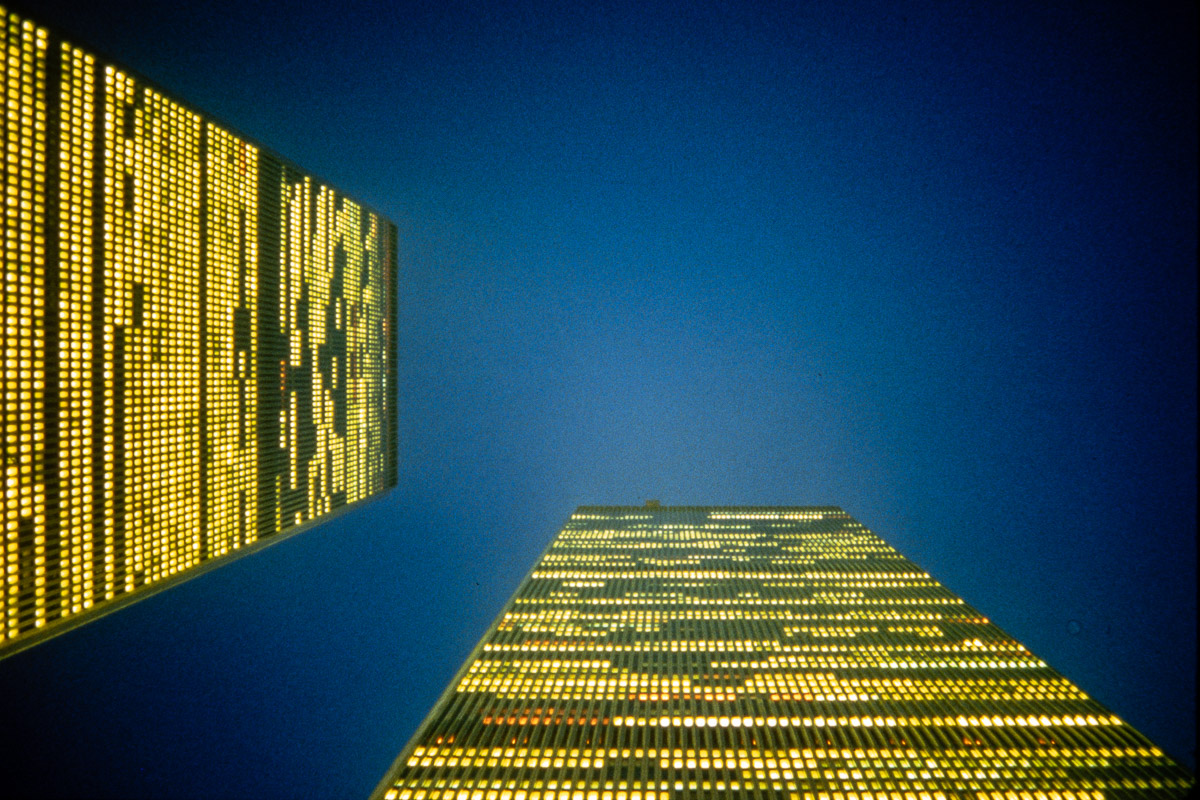

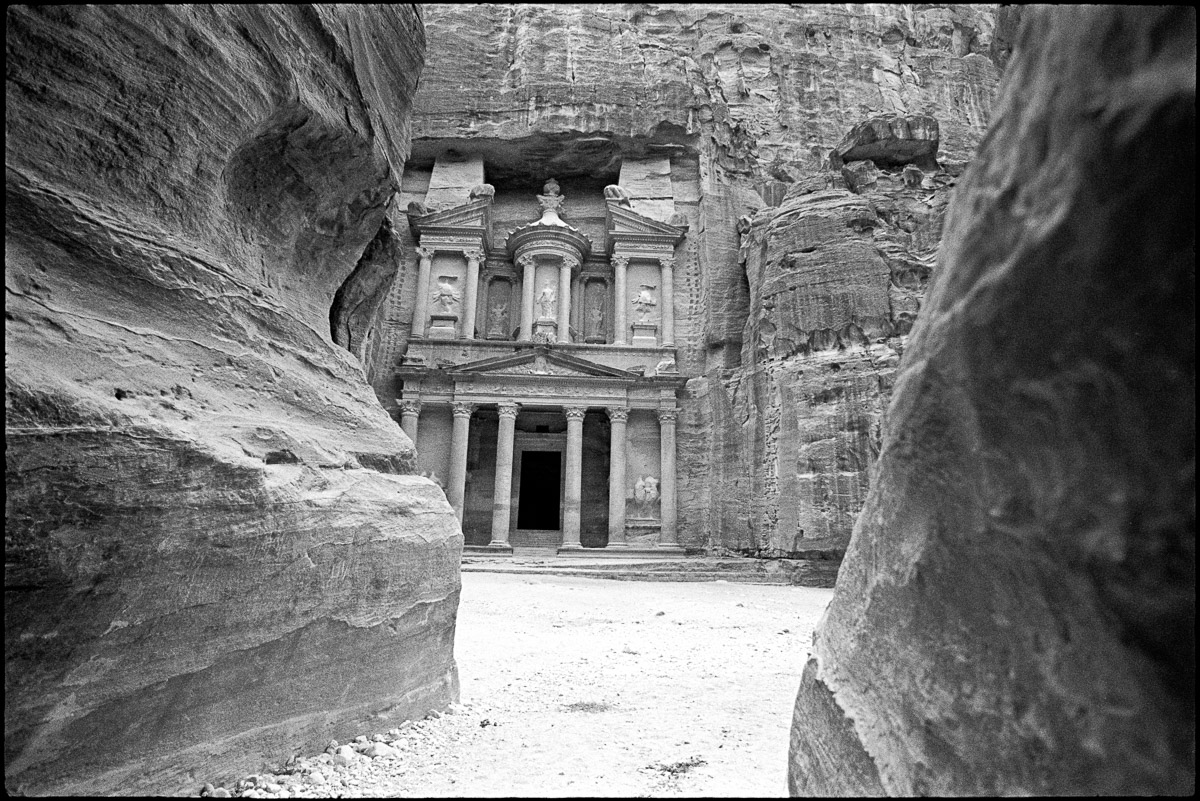

Can you tell the difference?

Which of these two photos was taken on film? Which one is digital?

Send me your answer, I'm curious to know what you think.

Click on the photos below to view them full screen.

All the photos displayed on this website are copyright protected © Sebastien Desnoulez. No use allowed without written authorization.

Legal notice

About the Author

Sebastien Desnoulez is a professional photographer specializing in architecture, landscape and travel photography. Trained in photography in the mid-1980s, he covered Formula 1 races and reported from around the globe before devoting himself to a more demanding fine art photography practice blending composition, light and emotion. He also shares his technical expertise through hands-on articles for passionate photographers, built on a solid background in both film and digital photography.

Tags

I am represented by the gallery

Une image pour rêver